Was Esther Mordecai’s (Adopted) Daughter or His Wife?

Tuesday, May 22, 2018 at 2:41AM

Tuesday, May 22, 2018 at 2:41AM  Edwin Long's Queen Esther (1878)Over the past few years, any time I read an Old Testament passage—whether preparing a passage myself or listening to someone else—I always compare the Hebrew Masoretic Text (which is the basis for most modern Old Testament translations) with the Septuagint (or LXX, the 2nd century BC Greek translation of the Old Testament, primarily used by New Testament and Early Church writers).

Edwin Long's Queen Esther (1878)Over the past few years, any time I read an Old Testament passage—whether preparing a passage myself or listening to someone else—I always compare the Hebrew Masoretic Text (which is the basis for most modern Old Testament translations) with the Septuagint (or LXX, the 2nd century BC Greek translation of the Old Testament, primarily used by New Testament and Early Church writers).

Most of the time, there’s not a significant amount of difference but the basic kind of variations to be expected when literature is translated from one language to another. However, occasionally, intriguing differences stand out, such as the one below I discovered recently.

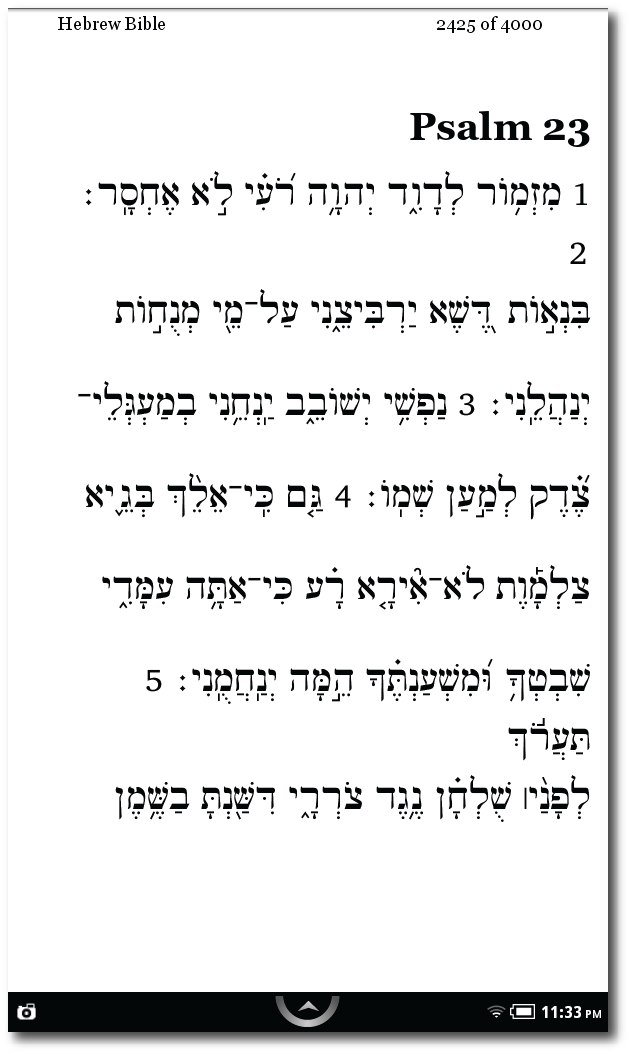

A week ago Sunday, I was able to attend my home church in Louisiana with my mother for Mother’s Day. The sermon that morning was drawn from the second chapter of Esther, and it was v. 7 that jumped out at me when I compared it to the LXX using Accordance on my iPad. The pastor was reading from the New King James Version, which I will quote below as a decent English representation of the Hebrew text. I’ve included notes for a couple of words significant to this discussion.

“Mordecai was the legal guardian of his cousin Hadassah (that is, Esther), because she had no father or mother. The young woman had a beautiful figure and was extremely good-looking. When her father and mother died, Mordecai had adopted [לָקַח/laqach, literally “taken”] her as his own daughter [בַּת/baṯ].”

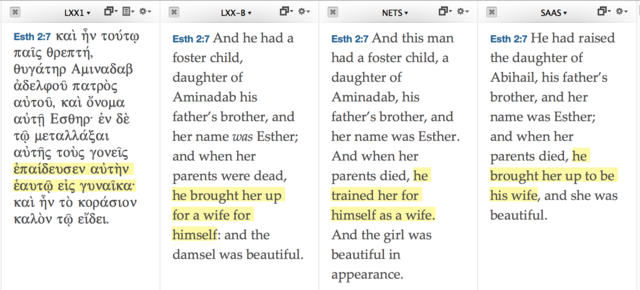

What jumped out when looking at the LXX was the replacement of בַּת (daughter) with γυνή/gynē (wife)! Mordecai had taken Esther as his wife? And technically, he had not taken Esther as his wife, but as the LXX indicates in the phrase, “ἐπαίδευσεν αὐτὴν ἑαυτῷ εἰς γυναῖκα,” Mordecai “had instructed/trained her to be a wife for himself.”

Compare the LXX with three English translations of Est 2:7—

Of course, at this point, I was no longer concentrating on the sermon but scrambling to look at commentaries to see if there was any mention of this major distinction in regard to Esther’s relationship to her cousin, Mordecai. I consulted a half dozen or so current biblical commentaries in Accordance, and none of them mentioned the discrepancy between the Hebrew and Greek versions of the Old Testament--until I looked at Levenson’s volume in the Old Testament Library series, where he writes,

“The Greek version and rabbinic midrashim tend to see the relationship between Mordecai and Hadassah (Esther) as one of marriage, and ancient custom does indeed know of adoption in anticipation of matrimony (cf. Ezek. 16:1–14).”

There was a footnote in Levinson’s commentary on Esther that led me to the Babylonian Talmud where Neusner translates the appropriate section (Meg 13.1) as follows:

VI.1 A. “...and when her father and mother died, Mordecai took her to himself as a daughter.”

B. One taught in the name of R. Meir: Do not read [it] “as a daughter” (le-vat), but rather as a wife (le-vayit).

C. And similarly it says, “and the poor man had nothing except one small lamb that he owned and fed, and it grew up together with him and with his children; it ate from his bread, and drank from his cup, and lay in his bosom, and it was like a daughter” (2Sa. 12:3). Because it lay in his bosom is it called a daughter (bat)? Rather [it should be called] a wife (bayit).

D. Here, too, [in Esther, the word “as a daughter” (bat) should be understood to mean] “as a wife” (bayit).

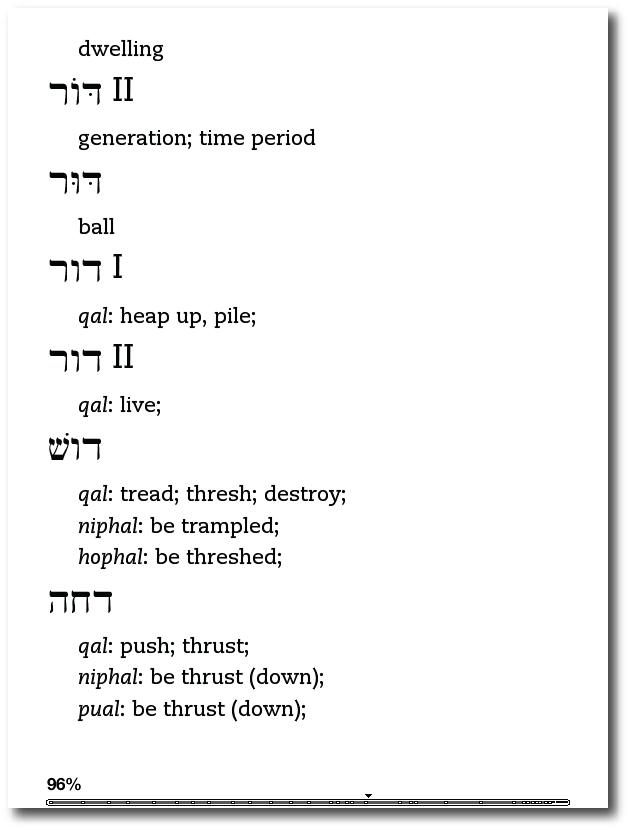

This is interesting because the rabbis are suggesting that the Hebrew, which obviously does not contain vowel pointing when they are reading it, should read Esther’s role not as daughter (בַּת/baṯ) but as wife (בַּיִת/bayit). Of course, my understanding of בַּיִת relates it to meaning house, household, or family, so perhaps this is somehow synonymous with wife as Hebrew is usually more functional than ontological in its use of language. Or perhaps I'm "reverse-transliterating" Neusner's Hebrew incorrectly. If anyone can offer insight, I’d appreciate that in the comments.

However, this matter of unpointed Hebrew would also explain why the LXX reads that Mordecai had instructed/taught (παιδεύω/paideuō) Esther rather than the Masoretic Hebrew understanding of taken (לָקַח/laqach). Obviously, the LXX translators understood the unpointed לקח as לֶקַח/leqaḥ (taught) rather than לָקַח/lāqaḥ (taken).

Incidentally, I often hear the LXX criticized for being too interpretive of the Hebrew text, but the vowel points added to the Hebrew by the Masoretes are often just as interpretive. The LXX probably translates Esther 2:7 as it was understood in Jewish thought around 200 BC. This understanding is backed up by the later rabbinic testimony found in the Talmud. Evidently, by the time of the 10th century AD, Esther’s relationship to her cousin as wife and not daughter was either forgotten or re-interpreted when the Masoretic Hebrew text was finalized.

For the sake of modern readers, I should probably mention that there really would not have been any scandal around the idea of cousins marrying each other at this time. Race and tribe would have been the most important factor, so the fact that Esther was already part of Mordecai’s family made her a seemingly ideal mate in a time of exile. Esther is referred to as a girl in both Hebrew (נַעֲרָה/naʿarāh) and Greek (κοράσιον/korasion) versions of the story, so she was probably fairly young. Since her beauty is also mentioned, she had probably reached marriageable age by the time she is taken from Mordecai, but presumably the marriage had not been consummated yet as she was deemed a suitable canidate for Xerxes' harem.

So by this point, I believe I’ve convinced myself that Esther probably was brought up by Mordecai to be his wife as opposed to his merely being her legal guardian until she was of marriageable age. And that makes the story even more tragic, doesn’t it? This reading certainly explains Mordecai’s angst over Esther as he continually loiters outside Xerxes’ harem (a dangerous thing to do) to see if he could find out how she was doing. Mordecai had not just lost a family member to a pagan king—he had lost his betrothed, someone to whom he had invested years of care and instruction, and he had lost his future. No doubt, Mordecai loved Esther on multiple levels; but in the end, his forced loss of her to a pagan king led to the salvation of the Jewish people in Persia. Mordecai’s personal loss was his people’s gain.

Esther,

Esther,  Hebrew Bible,

Hebrew Bible,  LXX in

LXX in  Faith & Reason

Faith & Reason