Previous posts:

Skeletons in the Family Closet, Part One: The Grandfather I Never Knew

Skeletons in the Family Closet, Part Two: A Shooting in Phillips County

Skeletons in the Family Closet, Part Three: Grief Upon Grief

This past Monday, as the sun was setting, I stood at the head of the grave of my great grandfather, William P. Mansfield. I did not know that the gates of Maple Hill Cemetery in Helena, Arkansas, closed at 5 PM, but I had come this far and locked gates did not stop me—I had simply climbed over the fence a few minutes earlier.

As I stood before the paltry grave marker, making a mental note to one day replace it, I patted the top of the rough concrete slab and said, “Don’t worry, William, I’m going to make certain the world knows what really happened.”

[2023 update: Look for a fifth installment to this post written in 2023. When I offered the above sentiment, I considered my great grandfather a victim, and his killer, Lester Yeager, a villain. History is often more complicated than one might imagine, as I will detail in the fifth installment. And, no, I will not be getting William a nicer headstone after what I have learned in the last decade since writing this post. He's lucky to have what he has.]

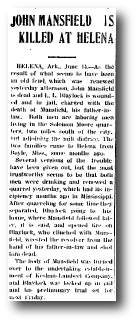

As I have earlier recounted, around midnight on April 7, 1920, my great grandfather, William Porter Mansfield, showed up at the home of a Phillips County, Arkansas, deputy sheriff named Lester Yeager. According to Yeager’s testimony, angered over a disputed timber contract, William Mansfield started firing a gun before Yeager could even open the door. Yeager returned fire, shooting my great grandfather four times. He died the next day. There were no other witnesses to offer an alternative version for the events that took place, so although charged with first degree murder, Yeager never actually stood trial for this crime.

I would discover, however, that the truth of these circumstances were much more sinister than what Yeager described or what I ever imagined. It seemed scandalous enough that my great grandmother would marry Yeager, her husband’s killer, eight months after the event took place. And yet with what I know now, that act seems even more egregious and inexcusable.

All families have secrets. If you dig deep enough you’ll find skeletons of your own. Family hurts and scandals are best covered up and forgotten by those immediately attached to them. I would have never known what really happened in Phillips County, Arkansas, to my family, had there not been a trial with significant newspaper coverage.

With a gut-level feeling that there was much more to this story than what was at face value, I traveled to Helena, Arkansas, in Phillips County earlier this week. I found this once-bustling boom town on the Mississippi River to be a shadow of its former glory. At the turn of the century there was great opportunity to make a living or even a fortune from cut timber; and after the timber was cut, many a landowner became rich from the cotton grown on his land. In fact, we spent the night in the only decent guest accommodations in Helena: the Edwardian Inn. This elaborate mansion was built in 1904 after its initial owner made over $5 million in a little over a year’s time. That’s $5 million in 1904 dollars, mind you.

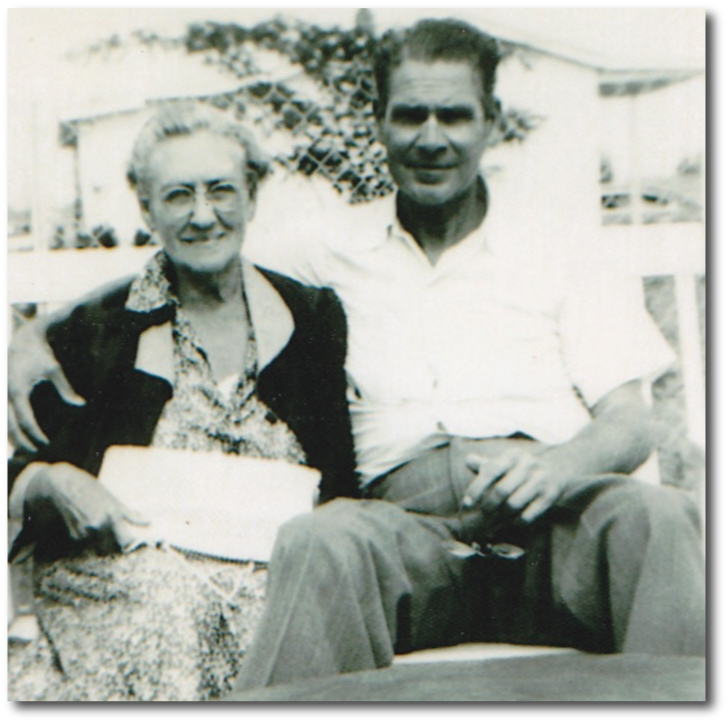

Anyone alive today who still remembers my great grandmother Daisy did not know her with the last name "Yeager" or even "Mansfield." They remember her as Daisy Mooney. A vague family memory dictated that she met her last husband Sam Mooney, a railroad detective, while visiting her previous husband at Cummins Prison in Arkansas. Of course, no one in our family remembered the name Yeager, so it had been assumed that it was the Mansfield husband (no one remembered the name William either).

Yet knowing that William was killed in 1920, I knew that if there were any truth to the story that Daisy had a husband in prison, it would have to be Yeager. Yet I also knew Yeager did not go to trial for killing my great grandfather. I knew there had to be something else, so I kept looking.

Combing legal documents in the Phillips County CourthouseKnowing that the next record I had for Daisy placed her in Little Rock in 1928, I was expecting to have to go through a few years worth of records in the handwritten criminal docket book. I did not expect to find something else in 1920, but there it was.

Combing legal documents in the Phillips County CourthouseKnowing that the next record I had for Daisy placed her in Little Rock in 1928, I was expecting to have to go through a few years worth of records in the handwritten criminal docket book. I did not expect to find something else in 1920, but there it was.

The circuit court judge came to Phillips County twice a year--in April and in October. For the latter session in 1920, I found Lester Yeager's name again. The charge was quite alarming: carnal abuse. Earlier that morning, while sifting through records in the courthouse, I'd discovered Lester Yeager's July 1920, resignation letter from the sheriff's department. I'd wondered about it, but people transition out of occupations all the time. By itself it didn't mean anything. Now, I really started to wonder if there might be a connection.

The docket did not list the victim, but it did list the verdict: guilty with a sentence of 21 years in the state penitentiary.

It took us a while to find the actual documents for the trial because no one at the courthouse could remember how files from that time were arranged. We had the case number though: 4684. We began our "needle in a haystack" search combing through thousands of cases until we discovered it.

I wrote a few weeks ago that my jaw dropped when I learned that my great grandmother, Daisy, married her husband's shooter, Lester Yeager. My jaw dropped again when I saw the name of his victim of "carnal abuse": Elizabeth Mansfield, the daughter of William and Daisy Mansfield and the older sister of my grandfather, John.

Now, if you've read this far into this sordid tale, I want to make certain you are clear on the chronology of these events:

from the Helena Daily World, November 8, 1921December 1919: Lester Yeager (a 39-year-old deputy sheriff) begins having sexual relations with Elizabeth Mansfield (a twelve-year-old girl). This will continue until at least March, 1920, and in the process, Elizabeth becomes pregnant. [2023 note: this turned out not to be true. Aunt Beth had lied about who the father was.]

from the Helena Daily World, November 8, 1921December 1919: Lester Yeager (a 39-year-old deputy sheriff) begins having sexual relations with Elizabeth Mansfield (a twelve-year-old girl). This will continue until at least March, 1920, and in the process, Elizabeth becomes pregnant. [2023 note: this turned out not to be true. Aunt Beth had lied about who the father was.]

April 7, 1920: William Mansfield shows up at the door of Lester Yeager around midnight. Gunfire is exchanged and William dies a day later. Lester claims that the dispute was over a timber contract, but there are no witnesses. Based on what we now know--Aunt Beth may have possibly been starting to "show"--I think he went to confront Lester, possibly even kill him. Lester is a deputy sheriff with powerful connections. Not only does he seem to have a good relationship with Sheriff Kichena, later that year, George Yeager will be elected mayor (I have not yet verified a family connection, but it’s an interesting coincidence). Although Lester Yeager is arrested for first degree murder, he never goes to trial for this act--the case is dismissed.

July, 1920: Yeager resigns as a deputy sheriff.

September to December 1920: Aunt Beth gives birth to a baby that is put up for adoption. Court documents reveal that she did indeed give birth. The date span I’ve listed here is a probable guess.

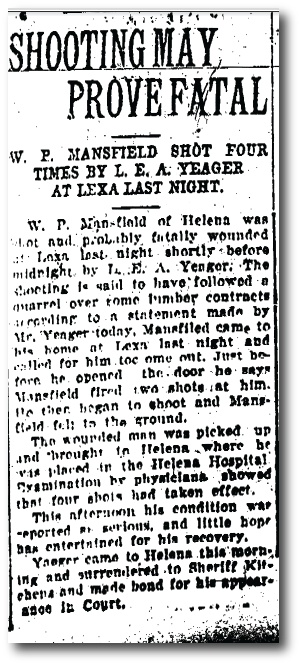

October 27, 1920: Lester Yeager is arrested for "carnal abuse." The trial is postponed until 1921; Yeager is released on $500 bond.

December 20, 1920: On the day after his 40th birthday, Lester marries Daisy Mansfield, the wife of the man he killed in April and the mother of the girl he has sexually abused. Note that the marriage occurs after his arrest for sexually abusing Elizabeth.

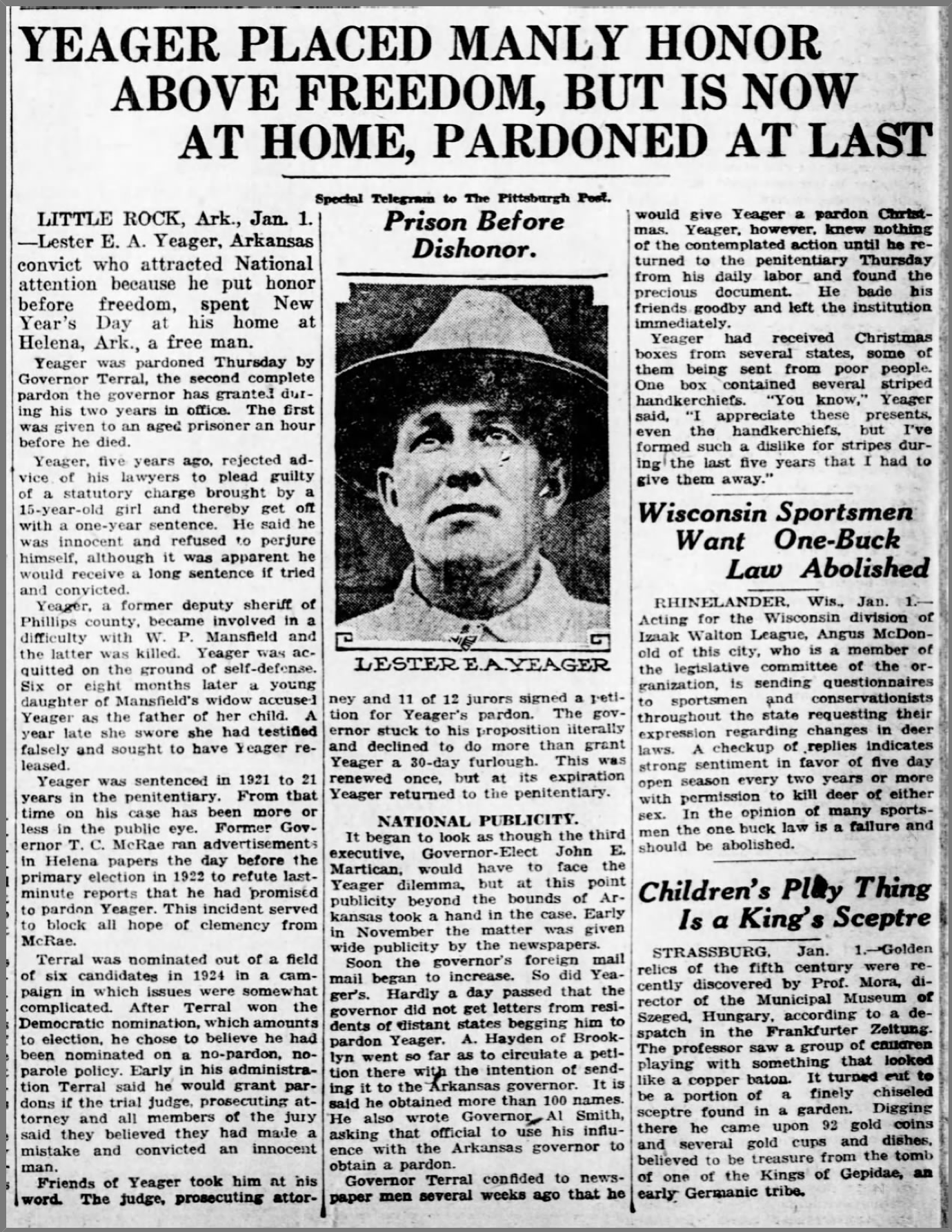

November 8, 1921: After less than a day of testimony and a 15-minute jury deliberation, Lester Yeager is found guilty of carnal abuse against Elizabeth Mansfield and sentenced to 21 years in the state penitentiary, the maximum sentence. His lawyers immediately file a motion for a new trial, but I have found no record that this was ever even considered. More than likely, the judge simply threw it out. The last mention of Yeager I could find in the newspapers occurred on November 15, 1921. The article mentioned that Yeager, unable to pay his bond (his money undoubtedly exhausted on his unsuccessful legal defense), was sitting in the Helena jail waiting for the judge’s decision on his motion for a new trial. More than likely, Yeager never saw another day as a free man again—thankfully. [2023 update. Fortunately, this is not true. When the truth is found out as to who the actual father of Beth's child is, Yeager is pardoned.]

Court documents and newspaper accounts can tell us the “what” of history, but they don't always tell us the “why.” As I’ve thought through these events, outside of some incredibly forceful coercion, I can’t conceive of any reason that would justify Daisy’s decision to marry this man knowing what he did to her husband and her daughter. Of course, more than likely, Daisy may have been involved with this man, too, with one bad decision leading to another. If so, she would unfortunately not be the first wife to ignore abuse taking place right in her own home. And unless I one day discover a diary or some kind of personal correspondence chronicling these events, I doubt that I’ll ever have anything more than my own speculation for the reasons behind her actions.

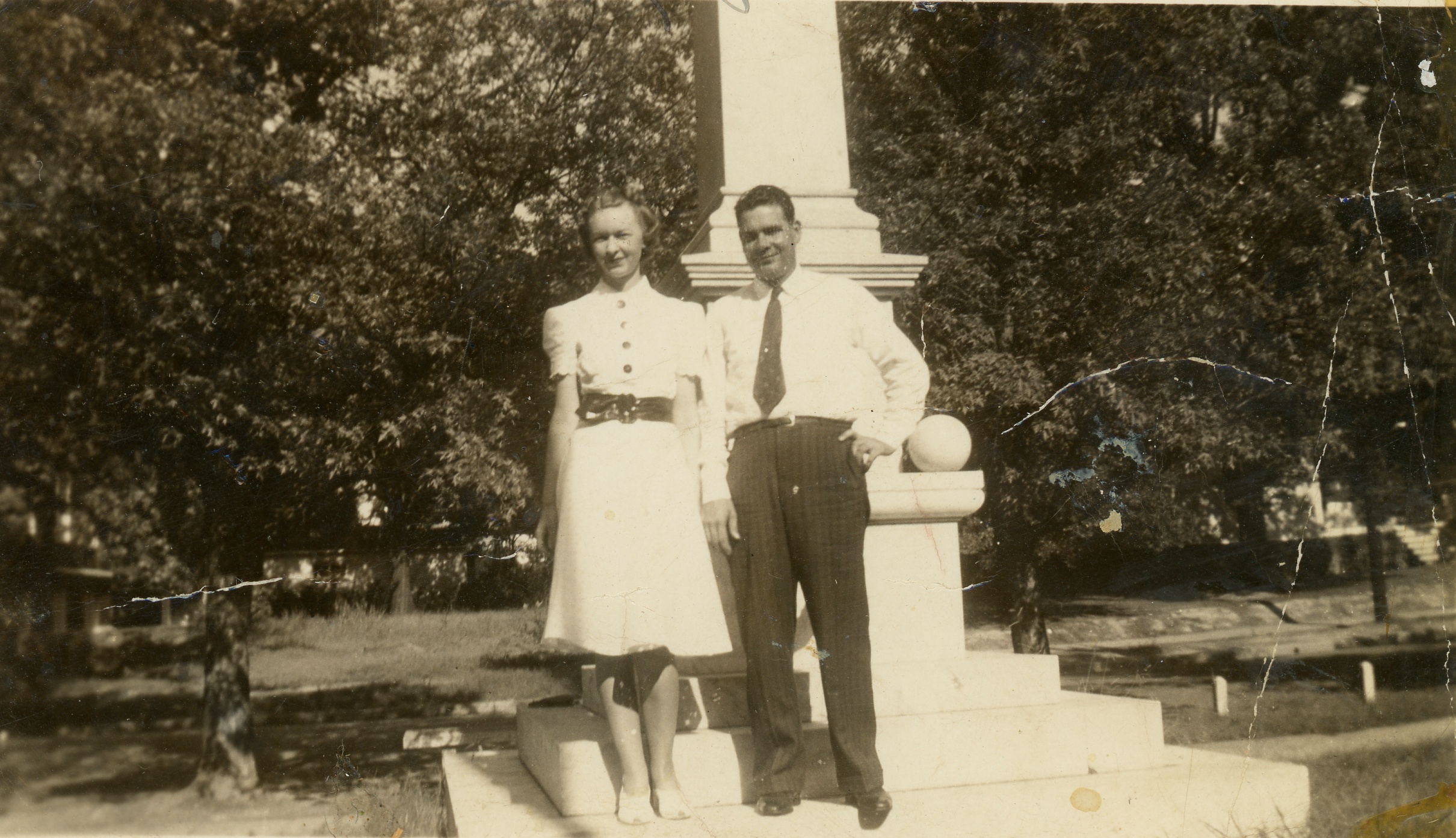

Daisy and Lester Yeager, 1921, in Lexa, Arkansas.

Daisy and Lester Yeager, 1921, in Lexa, Arkansas.

[2023 update: since writing this post over a decade ago, we now know what Lester Yeager looked like, and I'm not certain the above man is him. I had assumed it was probably him because the year at the bottom of the photo. However, this is not from Daisy's hand. There is a strong resemblance of this man to my own father, and I now believe this may be the only surviving photo of William Mansfield. But I go back and forth on this.]

I also think of my grandfather, John—Beth’s younger brother. His wife and my grandmother, Maurene, said that he was an extremely smart man—very gifted in regard to anything mechanical. But that description was always followed by “But he could have been so much more if he had been able to get more than a grade school education, and if he had not been so drawn to alcohol.” She said that John had told her that he had to drop out of school after the fourth or fifth grade to help support the family. Now we know why. His own father died trying to protect his family. His “stepfather” (if Yeager can even be called that) went to jail the following year. My grandfather John had to work to support his family. Like his sister, his childhood was also cut desperately short. Moreover, history does not record any positive male influence in his life during his formative teenage years.

As I contemplate these events, I wonder this: if my grandfather John had experienced a better childhood, would his adult life have turned out differently? Would he have been more responsible? Would he have not been so controlled by alcohol? Would I have ever met him?

Or would I even have been born at all?

There’s a clichéd question in philosophy that asks, “If you go back in time and kill your own grandfather, will you then cease to exist?” For me, the question is different, though—“If I could go back in time and prevent my great grandfather from getting killed, would I then cease to exist?”

The altered question pertains to my own existence because I am here because of my grandfather’s bad decisions, which I am convinced, were contributed to by an extremely disruptive childhood and dysfunctional (to put it mildly) family life. My grandfather, John, married Ena Prier, and they had four children. Then, with the youngest child only two years old, John left Ena for my grandmother, Maurene. My father, his two sisters, and I all owe our existence to the irresponsibility of this man.

And while this makes for interesting speculation about my own existence, none of my family history defines who I am. We are all responsible for our own decisions. In the end, I answer for myself; and although I make mistakes, I can’t blame them on my family tree.

If anything, my being here—my very existence—is the result of God’s grace. I am reminded of the Old Testament story of Joseph whose brothers sold him into slavery—a horrific action when he was very young. Later after he has risen to a position of prominence in Egypt, he tells his brothers, “You intended to harm me, but God intended it for good to accomplish what is now being done, the saving of many lives” (Gen 50:20, NIV). God didn’t force Joseph’s brothers to do what they did; they had clear intent and malice. Nevertheless, God, who could see the big picture of history, was moving in these same events, guiding Joseph so that despite his circumstances, a great amount of good would come about.

The Apostle Paul has a similar thought in the New Testament when he writes, “And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose” (Rom 8:28, NIV). I sometimes hear people talk about God as if he causes bad things to happen to us so that he can then turn around and bring good from it, or so that he can teach us something from it. This idea is usually followed by the inane statement, often quoted as if it's scripture itself (it's not): "Everything happens for a reason." I believe that’s a distortion, and I refuse to accept that kind of fatalism. Bad things happen for a variety of reasons or no reason at all. Trying to find divine purpose behind every tragedy will drive a person mad or create feelings of anger and distrust toward God. Nevertheless, I know that God can take the bad events that happen in our lives and turn them into very positive and good results—on an exponential scale. This is the very essence of redemption.

Yes, my existence partly owes itself to the fact that my grandfather could be a bit of a scoundrel at times, and he was responsible for his own actions. Nevertheless, I also believe that I am here as a part of God’s purpose—not just me, but my father, his sisters and all my cousins and their children who can trace their lineage back to the Mansfields I’ve been writing about. If we open ourselves to God’s will in our lives, he will work for the good of us and for those with whom we come into contact.

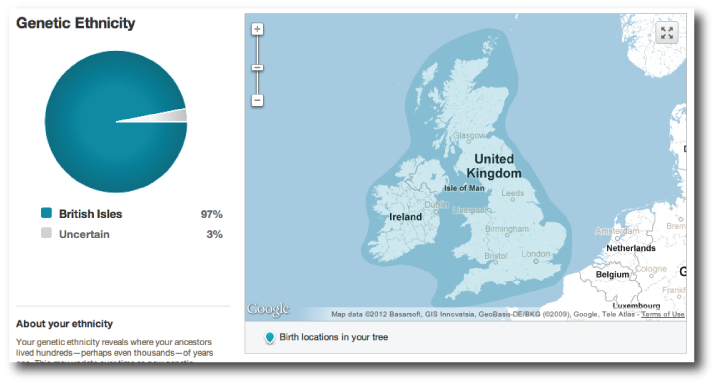

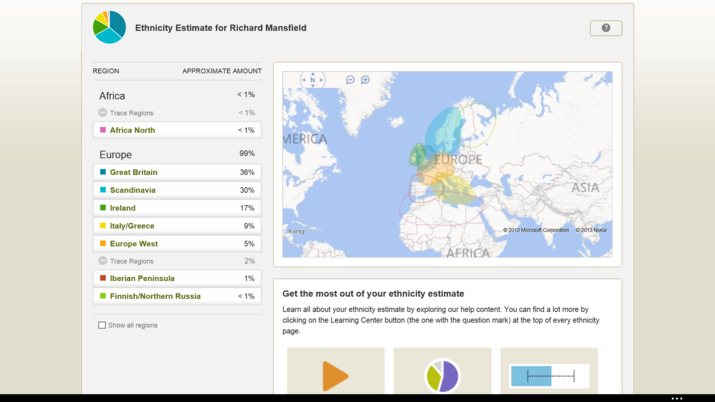

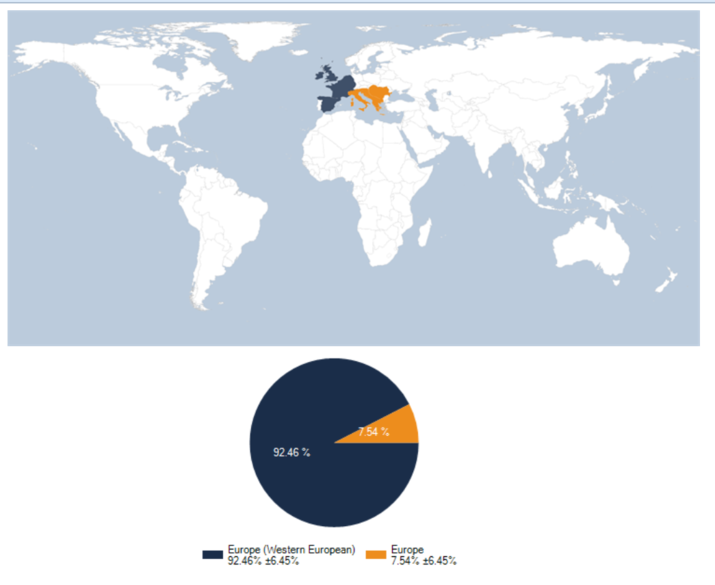

I confess to being fascinated with the lives of my forebears in spite of the disconcerting details. My DNA tells me that they are a part of me, and I am a part of them. But I am also something more. In the end, I am my own person, and I am responsible for my words and my actions. I can choose to learn from the mistakes of previous generations and my own, and what I do with that information helps determine my own path.

Part 1: The Grandfather I Never Knew

Part 2: A Shooting in Phillips County

Part 3: Grief Upon Grief

Part 5: Prison Before Dishonor

Your questions, thoughts, comments and rebuttals are welcome below.

Monday, October 23, 2023 at 11:23AM

Monday, October 23, 2023 at 11:23AM  Previous posts:

Previous posts:

The ever-charismatic John, my grandfather, with Aubrey on the left and Beth on the right--around 1928The big question for me is what happened to the child put up for adoption. I'd like to eventually go back to Phillips County, Arkansas and pursue this question in the old courthouse records. Everyone involved is now long gone, so there should not be any objection for sake of privacy at this point. Interestingly, there are a number of photos from around this time of a family friend, Aubrey Tharp and her son, James, who was born (coincidentally) in 1920. Was James the son of Beth given up for adopton? I've got my DNA out there quite publicly in hopes that one day this mystery can be solved.

The ever-charismatic John, my grandfather, with Aubrey on the left and Beth on the right--around 1928The big question for me is what happened to the child put up for adoption. I'd like to eventually go back to Phillips County, Arkansas and pursue this question in the old courthouse records. Everyone involved is now long gone, so there should not be any objection for sake of privacy at this point. Interestingly, there are a number of photos from around this time of a family friend, Aubrey Tharp and her son, James, who was born (coincidentally) in 1920. Was James the son of Beth given up for adopton? I've got my DNA out there quite publicly in hopes that one day this mystery can be solved. family history,

family history,  genealogy in

genealogy in  Genealogy

Genealogy