Skeletons in the Family Closet, Part Five: Prison Before Dishonor

Monday, October 23, 2023 at 11:23AM

Monday, October 23, 2023 at 11:23AM  Previous posts:

Previous posts:

Part 1: The Grandfather I Never Knew

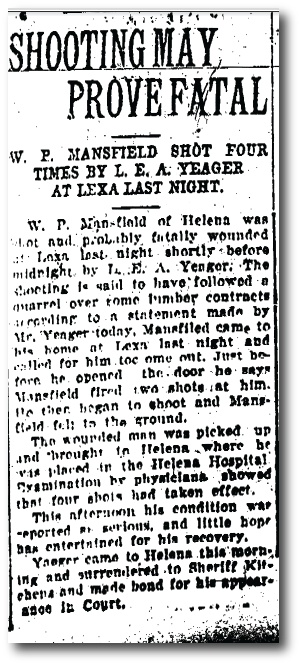

Part 2: A Shooting in Phillips County

Part 4: Confronting the Abhorrent Truth

This is a post I should have written years ago. Sometime around 2016, my cousin Cheryl (we share the same grandfather, John Mansfield, but different grandmothers if you've been following the story) had done some additional research and made a startling new discovery about the events that unfold in my previous posts.

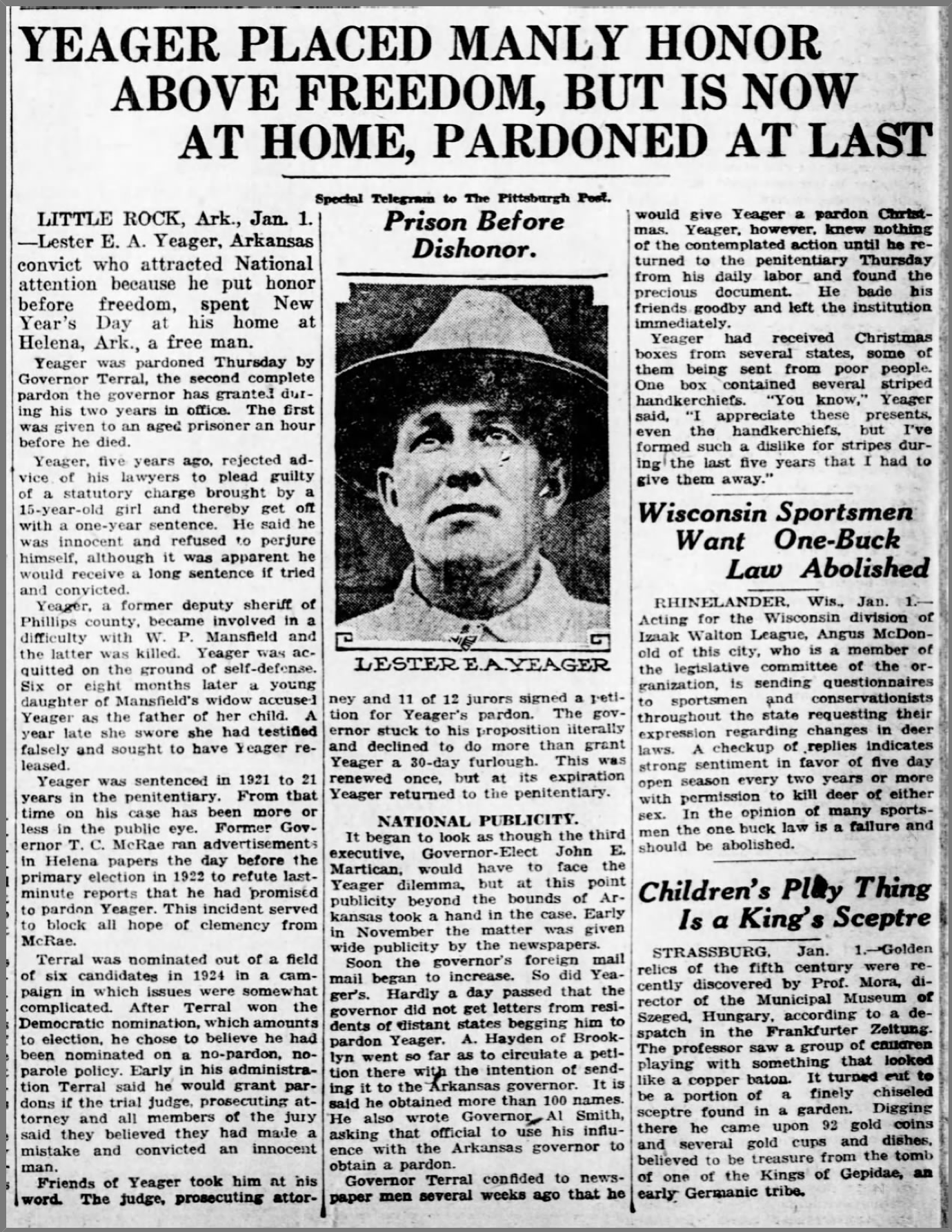

All of the intrigue and twists of this story came back into my life recently due to a series by reporter Ceilia Storey of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. She had come across the name Lester Yeager (the man who shot my great grandfather, William; married my great grandmother, Daisy; and was originally accused by my Aunt Beth of fathering her child) in writing another article. When Storey began researching Yeager, she came across century-old national news related to the century-old scandal as well as my blog posts linked above.

Here are the four posts by Celia Storey related to Lester Yeager, recently published in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. The fourth installment mentions my blog and me. If you're not a subscriber to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, you will have to sign up; but you can get 8 weeks for $1 and cancel anytime.

The woman they wouldn’t let into prison in 1923 Arkansas (Sept 17, 2023)

In crime-weary 1920s Arkansas, 2 governors let exonerated man linger in prison (Oct 1, 2023)

With Klan on the rise in 1920s, another Arkansas governor lets innocent deputy rot in prison (Oct 8, 2023)

Surprise evolves into dismay as Daisy Yeager’s descendant seeks 100-year-old truth (Oct 22, 2023)

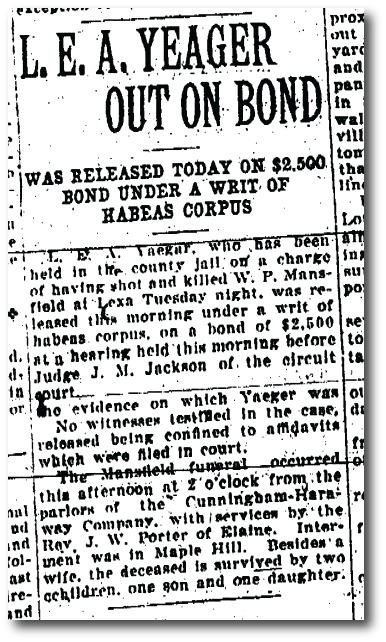

So to recap: in the Spring of 1920, my great grandfather, William Porter Mansfield, dies in a gunfight with Phillips County, Arkansas, deputy Lester Yeager. With a claim of self defense, Yeager does not go to jail for killing my great grandfather. Beth, the 13-year-old daughter of William and Daisy is found to be pregnant. She points the finger at Lester Yeager as the father, and he is arrested in October, 1920, for "carnal abuse." Beth gives the baby up for adoption. For reasons that are still not entirely clear, my great grandmother Daisy marries Yeager in December of that year. Yeager is offered a plea deal of one year in prison if he will plead guilty to the charges. He refuses, claiming his innocence, and is sentenced the next year to 21 years in the state prison.

When I last wrote about these events, over a decade ago, I thought this was the end of things. I assumed that Yeager died in prison. But as mentioned earlier, my cousin Cheryl unearthed new information a few years ago. If this story wasn't mind-blowing enough, there was still one more twist to be discovered.

Fast forward to 1923. Daisy divorces Lester while he's still in prison. Soon thereafter, her daughter Beth makes a startling confession: Yeager wasn't the father of her child, after all. Rather, William--her own father--was. On William's deathbed, he had convinced the impressionable Beth to tell the world that Yeager was the father of the baby.

As reported in The Pittsburg Post, Beth's official retraction reads as follows:

I, Elizabeth Mansfield, make the following statement of my own volition, without threats or promises of reward. I was the prosecuting witness and the only witness in the case in which L. E. A. Yeager was convicted in the Phillips circuit court of the charge of carnal abuse and was sentenced to 21 years in the state penitentiary. It was solely my testimony that convicted Yeager of that charge.

I did not testify to the truth at the time of the trial for the reason I had promised my father on his death bed that I would testify that Yeager was the guilty man.

The truth of the case is that my father was the father of my child and Yeager never had immoral relations with me at any time.

With Beth's retraction, the judge, prosecuting attorney, and 11 of the 12 jurors signed a petition for Yeager to be immediately pardoned and released from prison. This seems like a simple task. There was, however, a major problem: the current governor, T. C. McRae, and then his successor, Tom J. Terral, had both run on platforms promising no pardons.

In the meantime, Yeager, a model inmate, and with his accuser's retraction, had the full trust of the prison warden. He was the "trusty" at the gate for a period of time, allowing people in and out. He was given furloughs for work away from the prison. And he always came back. Yeager could have easily run and not returned. Odds are no one would have pursued him. However, he chose prison before dishonor. Perhaps it was his earlier occupation as a deputy sherriff that was so ingrained in Yeager that he refused to go against the due process of the law.

Fortunately for Yeager, after Terral lost his re-election bid, he formally pardoned the innocent man on Christmas, 1926. Lester Yeager had spent 5 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit.

There are still lots of unanswered questions. Why did Daisy marry Lester to begin with? When I thought Yeager was the bad guy in all this, I often wondered if perhaps something was going on between Daisy and Lester and by being married, she couldn't be forced to testify against him. But this makes less sense now that we know he was not guilty. What was the context of their divorce? Perhaps with Yeager sentenced to prison for 21 years, perhaps she just needed to find someone with whom she could have a future and could bring income into the household.

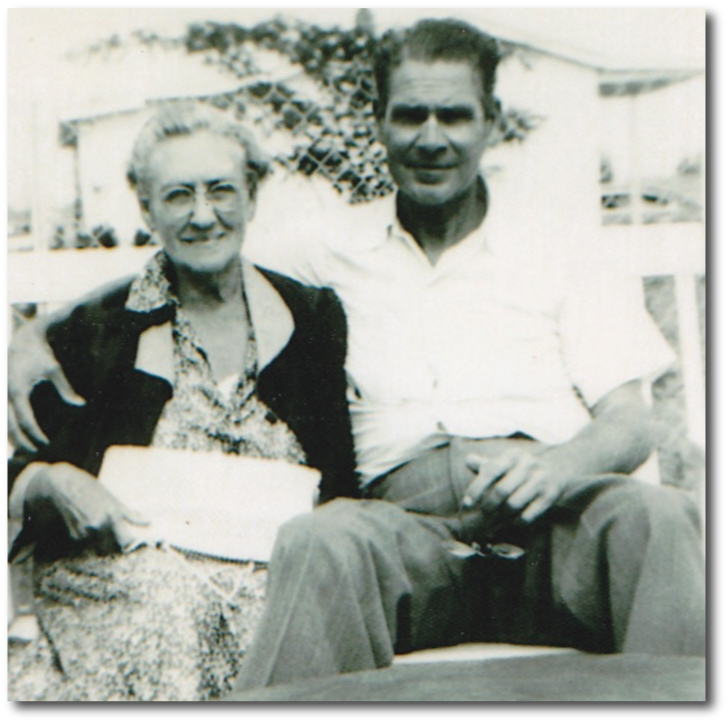

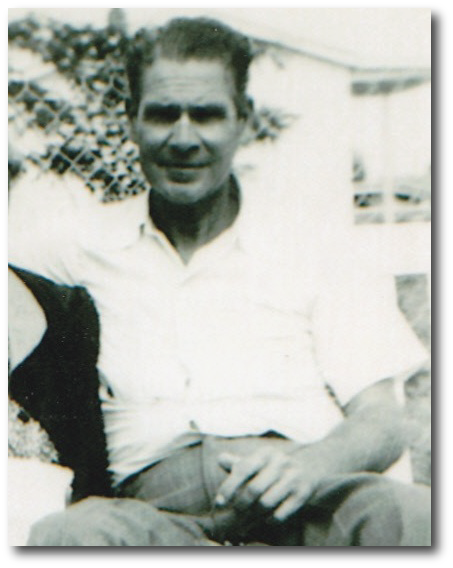

The ever-charismatic John, my grandfather, with Aubrey on the left and Beth on the right--around 1928The big question for me is what happened to the child put up for adoption. I'd like to eventually go back to Phillips County, Arkansas and pursue this question in the old courthouse records. Everyone involved is now long gone, so there should not be any objection for sake of privacy at this point. Interestingly, there are a number of photos from around this time of a family friend, Aubrey Tharp and her son, James, who was born (coincidentally) in 1920. Was James the son of Beth given up for adopton? I've got my DNA out there quite publicly in hopes that one day this mystery can be solved.

The ever-charismatic John, my grandfather, with Aubrey on the left and Beth on the right--around 1928The big question for me is what happened to the child put up for adoption. I'd like to eventually go back to Phillips County, Arkansas and pursue this question in the old courthouse records. Everyone involved is now long gone, so there should not be any objection for sake of privacy at this point. Interestingly, there are a number of photos from around this time of a family friend, Aubrey Tharp and her son, James, who was born (coincidentally) in 1920. Was James the son of Beth given up for adopton? I've got my DNA out there quite publicly in hopes that one day this mystery can be solved.

All of this needs more research, and then, I believe it would make quite the page-turner of a book. Stay tuned.

family history,

family history,  genealogy in

genealogy in  Genealogy

Genealogy