Genesis 18 (all verses below are from the NLT) tells the interesting story of three mysterious visitors who visit Abraham at the Oak of Mamre:

Genesis 18 (all verses below are from the NLT) tells the interesting story of three mysterious visitors who visit Abraham at the Oak of Mamre:

One day Abraham was sitting at the entrance to his tent during the hottest part of the day. He looked up and noticed three men standing nearby. When he saw them, he ran to meet them and welcomed them, bowing low to the ground.

“My lord,” he said, “if it pleases you, stop here for a while. Rest in the shade of this tree while water is brought to wash your feet. And since you’ve honored your servant with this visit, let me prepare some food to refresh you before you continue on your journey.” “All right,” they said. “Do as you have said.”

Then a few verses later (13), in the story, the reader learns unexpectedly that one of the three visitors is God when reading “Then the LORD said to Abraham.” The all-caps designation stands in place of the divine name for God, (יהוה / Yahweh), leaving no doubt to the reader that one of the strangers is God, the same God who will appear to Moses in Exodus 3.

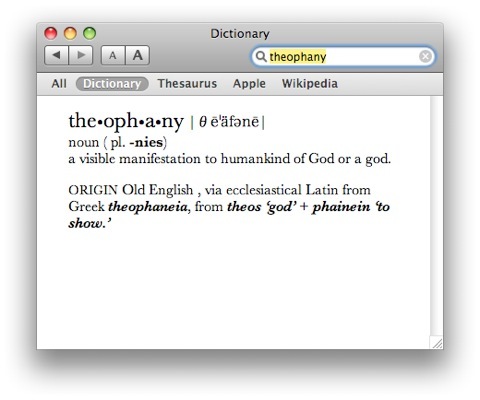

Ever since the early Christians began to work out the relationship of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in what would come to be known as the Trinity, many Christian writers, teachers, and preachers over the last two millennia have looked at Genesis 18 and have suggested that the three individuals who visited Abraham and his family at the Oaks of Mamre were, in fact, the three persons of the Trinity in physical manifestations. This is what is known in theological terms as a theophany, a physical manifestation of God for the purpose of relating to human beings.

The problem is that the Genesis text never specifically states the identity of the two other than beyond the one of them already identified as Yahweh. While some would like to equate Yahweh with God the Father exclusively, traditional Christian doctrine doesn’t make this claim either. In fact, from a Christian perspective, Yahweh is not limited to one person of the Trinity. See for example John 8:58, where Jesus essentially tells the Jewish leaders that they are in the presence of the same “person” who appeared to Moses at the burning bush in Exodus 3, but that doesn’t imply that the Father and Holy Spirit weren’t there, too.

The passage with Abraham in Genesis 18 is subtle. When encountering it for the first time, the reader/hearer may not expect initially that God is one of the visitors, although it is foreshadowed at the beginning of v. 1. Whether the other men who were present with Abraham were theophanies of the other persons of the Trinity or whether they were angels or even someone else, we simply don’t know because we weren’t privy to the entire conversation. And that’s the way the Bible generally works--less is more, if you will.

But not so with William P. Young’s book The Shack. In Young’s book, the main protagonist, Mackenzie Philips gets to sit around the dinner table eating greens and other good food, while picking the brain(s) of God, represented in three physical entities: Papa (Father God), represented by a large African American woman; Jesus (the Son of God), depicted as a Middle Eastern, bearded carpenter; and Sarayu (The Holy Spirit) who is a kind of wispy Asian woman. Mack is there in the Shack on the invitation of Papa because he’s never gotten over the death of his daughter at the hands of a serial killer years earlier. Because of this, not only does he blame himself, he also blames God.

But not so with William P. Young’s book The Shack. In Young’s book, the main protagonist, Mackenzie Philips gets to sit around the dinner table eating greens and other good food, while picking the brain(s) of God, represented in three physical entities: Papa (Father God), represented by a large African American woman; Jesus (the Son of God), depicted as a Middle Eastern, bearded carpenter; and Sarayu (The Holy Spirit) who is a kind of wispy Asian woman. Mack is there in the Shack on the invitation of Papa because he’s never gotten over the death of his daughter at the hands of a serial killer years earlier. Because of this, not only does he blame himself, he also blames God.

That’s a very brief synopsis of the book, and my hunch is--since I’m so late to the game with this review--that most readers of This Lamp know all this anyway. I’m writing this review because I’ve received questions and emails since last Fall asking what I think of The Shack. By simply being able to point people to this page, I won’t have to repeat myself so much.

Kathy and I listened to the unabridged audio version of The Shack in December while we were traveling to Louisiana and back for Christmas. I don’t own a physical copy of the book, so I won’t be able to quote it verbatim, but it doesn’t really matter. I can still offer my general impression and point readers to other sources.

You need to know, up front, that I don’t think very highly of The Shack on multiple levels. I am certain that some of you will think I’m just being theologically picky, that I’ve let formal study of the Bible make me into some kind of doctrinal do gooder who can’t allow my imagination to see God in creative ways. If you think that, you simply don’t know me well. But don’t just ask me about this book, ask my wife Kathy. She may be less charitable than me.

But let me start by being charitable. Let me start by saying that William P. Young seems to be a really great fellow. At the end of our audio version of The Shack we were able to listen to an extended interview with Young. His motives seem to be nothing more than sincere. At the very least, he is certainly the benefactor of fortunate circumstances with the sale of The Shack into the millions of copies at this point, and no doubt many of the publishers who turned him down greatly regret doing so.

Furthermore, I don’t think that Young was attempting to be unbiblical, let alone introduce heresy into his novel. Nevertheless, he did.

So much has been written about the doctrinal error in The Shack, I started not to even comment on it. One can easily run a Google search for “The Shack” and “heresy” and find a multitude of pages, so I doubt I could top what has already been done. However, let me reproduce here three of Norman Geisler’s fourteen errors in The Shack. Geisler may not win an award for best webpage layout, but he offers a strong theological critique for Young’s work.

Problem Four: An Unbiblical View of the Nature and Triunity of God

Problem Four: An Unbiblical View of the Nature and Triunity of God

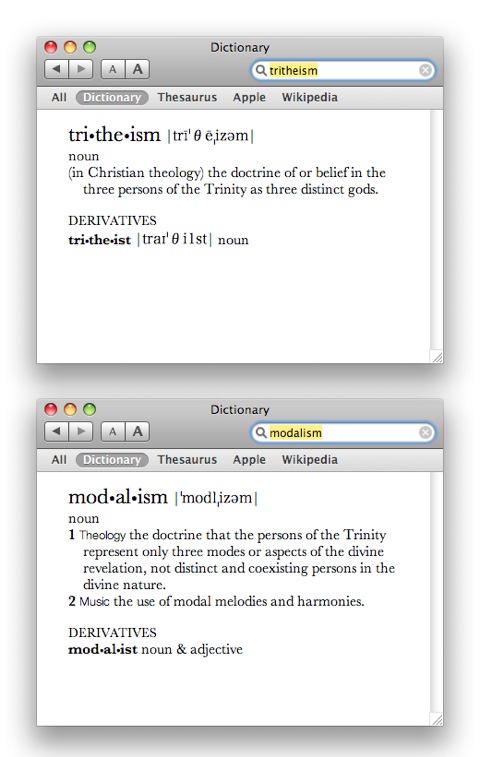

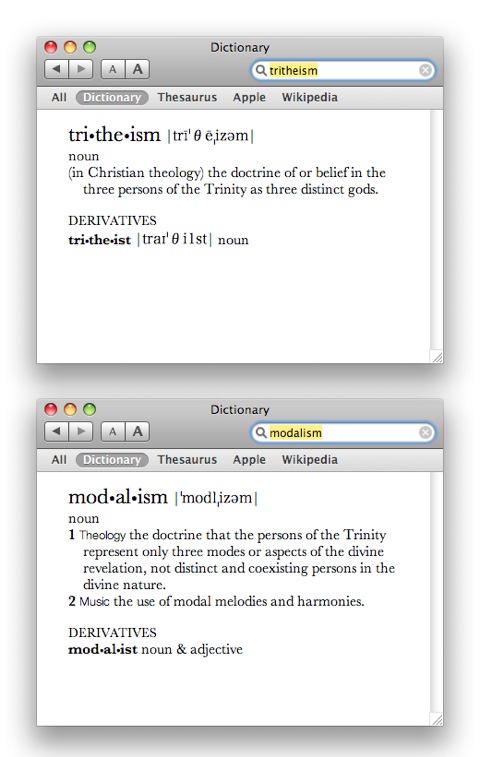

In addition to an errant view of Scripture, The Shack has an unorthodox view of the Trinity. God appears as three separate persons (in three separate bodies) which seems to support Tritheism in spite of the fact that the author denies Tritheism (“We are not three gods” ) and Modalism (“We are not talking about One God with three attitudes”—p. 100). Nonetheless, Young departs from the essential nature of God for a social relationship among the members of the Trinity. He wrongly stresses the plurality of God as three separate persons: God the Father appears as an “African American woman” (80); Jesus appears as a Middle Eastern worker (82). The Holy Spirit is represented as “a small, distinctively Asian woman” (82). And according to Young, the unity of God is not in one essence (nature), as the orthodox view holds. Rather, it is a social union of three separate persons. Besides the false teaching that God the Father and the Holy Spirit have physical bodies (since “God is spirit”—Jn. 4:24), the members of the Trinity are not separate persons (as The Shack portrays them); they are only distinct persons in one divine nature. Just as a triangle has three distinct corners, yet is one triangle. It is not three separate corners (for then it would not be a triangle if the corners were separated from it), Even so, God is one in essence but has three distinct (but inseparable) Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Problem Five: An Unbiblical View of Punishing Sin

Another claim is that God does not need to punish sin. He states, “At that, Papa stopped her preparations and turned toward Mack. He could see a deep sadness in her eyes. ‘I am not who you think I am, Mackenzie. I don’t need to punish people for sin. Sin is its own punishment, devouring you from the inside. It is not my purpose to punish it; it’s my joy to cure it’” (119). As welcoming as this message may be, it at best reveals a dangerously imbalanced understanding of God. For in addition to being loving and kind, God is also holy and just. Indeed, because He is just He must punish sin. The Bible explicitly says that” the soul that sins shall die” (Eze. 18:2). “I am holy, says the Lord” (Lev. 11:44). He is so holy that Habakkuk says of God, “You…are of purer eyes than to see evil and cannot look at wrong…” (Hab. 1:13). Romans 6:23 declares: “The wages of sin is death….” And Paul added, “‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay’ says the Lord” (Rom. 12:19).

In short, The Shack presents lop-sided view of God as love but not justice. This view of a God who will not punish sin undermines the central message of Christianity—that Christ died for our sins (1 Cor. 15:1f.) and rose from the dead. Indeed, some emergent Church leaders have given a more frontal and near blasphemous attack on the sacrificial atonement of Christ, calling it a “form of cosmic child abuse—a vengeful father, punishing his son for offences he has not even committed” (Steve Chalke, The Lost Message of Jesus, 184). Such is the end of the logic that denies an awesomely holy God who cannot tolerate sin was satisfied (propitiated) on behalf of our sin (1 Jn. 2:1). For Christ paid the penalty for us, “being made sin for us that we might be made the righteousness of God through him” (2 Cor. 5:21), “suffering the just for the unjust that He might bring us to God” (1 Pet. 3:18).

Problem Six: A False View of the Incarnation

Another area of concern is a false view of the person and work of Christ. The book states, “When we three spoke ourself into human existence as the Son of God, we became fully human. We also chose to embrace all the limitations that this entailed. Even though we have always been present in this universe, we now became flesh and blood” (98). However, this is a serious misunderstanding of the Incarnation of Christ. The whole Trinity was not incarnated. Only the Son was (Jn. 1:14), and in His case deity did not become humanity but the Second Person of the Godhead assumed a human nature in addition to His divine nature. Neither the Father nor Holy Spirit (who are pure spirit--John 4:24) became human, only the Son did.

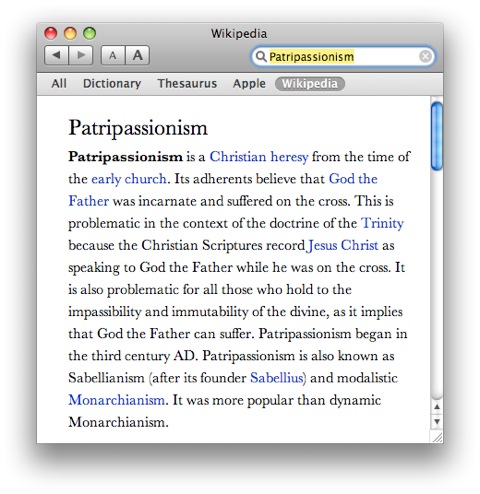

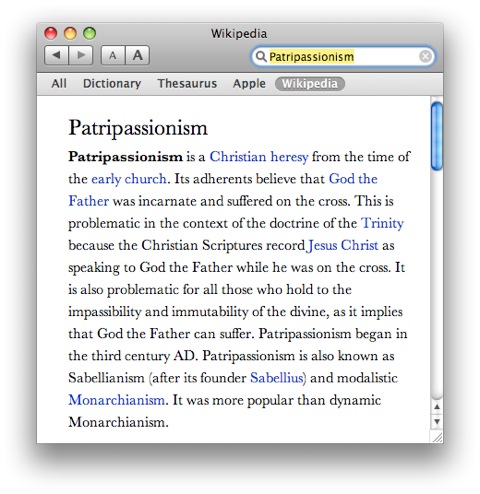

Look, I admit that understanding the nature of God--understanding the Trinity--is not the easiest of subjects. But it amazes me to hear from so many Christians “After reading The Shack, I think I finally understand the Trinity!” Well, no you don’t. You’ve merely become familiar with Young’s distortion of it. Again, I don’t think Young set out to distort a doctrine like that of the Trinity. I just don’t think he was able to write this kind of story without introducing error. And there’s lots of places I could go on about other weird representations of God (like Papa [the God the Father character] showing off his wounds, a textbook example of the heresy of patripassionism, which Geisler also notes), but where does one really stop? For those who want to read further on these kinds of issues--and really you should--there are links at the bottom of this post.

Look, I admit that understanding the nature of God--understanding the Trinity--is not the easiest of subjects. But it amazes me to hear from so many Christians “After reading The Shack, I think I finally understand the Trinity!” Well, no you don’t. You’ve merely become familiar with Young’s distortion of it. Again, I don’t think Young set out to distort a doctrine like that of the Trinity. I just don’t think he was able to write this kind of story without introducing error. And there’s lots of places I could go on about other weird representations of God (like Papa [the God the Father character] showing off his wounds, a textbook example of the heresy of patripassionism, which Geisler also notes), but where does one really stop? For those who want to read further on these kinds of issues--and really you should--there are links at the bottom of this post.

On a completely different level, The Shack doesn’t work for me simply because overall, it’s not good literature. Let me qualify that statement. I’ll admit up front that everything leading up to Mack’s entering the shack where his dialogue with God begins kept my keen attention. It was a tragic story about the loss of his daughter and his estrangement from God, and one that I was really interested in. And I would also point to Mack’s vision (or whatever you want to call it) in which he was reconciled to his earthly father--powerful stuff.

Unfortunately, it’s the most significant part of the book--his encounter and dialogue with the persons of the Godhead--which not only are full of bad theology, but really are the weakest narrative parts of the whole story. The dialogue is overblown, repetitive, and pretentious. If you want good theological dialogue, I recommend Peter Kreeft (see here and here). But if it’s true that George Lucas is incapable of writing realistic romantic dialogue, the same can be said for William P. Young when it comes to religious dialogue.

Besides that, there is too much content in the story that’s just plain weird or cheesy. The ongoing joke about Mack’s potential flatulence causing Papa (God the Father, as you’ll remember) to refuse him any more greens at dinner was more weird than humorous to both Kathy and me. Papa laughing at Jesus and calling him “Butterfingers” when he let slip a casserole dish, letting it come crashing to the floor seemed not only odd, but also introduced another doctrinal error. Essentially Young has Jesus err, something the Bible says he was incapable of doing. Would this also mean that Jesus occasionally smashed his thumb during carpentry work in Nazareth? Such a thought or question might not even matter to most reading this, but the implications start to get unsettling.

I had to grimace and shake my head when Mack opened his nightstand drawer in his bedroom at the shack and found a Gideon’s Bible. Ha ha ha. To me, that’s the kind of “gimmick” that distracts more than adds to the story. Further, when Jesus and Mack needed to walk to the other side of the lake, I knew it was coming before Young said it--sure enough, they would walk across the water! What else would you do if you were with Jesus? It’s these kind of gee whiz moments that I felt were bordering on immature and simply not needed in the story.

And should I even go into how Mack’s conversations with Papa in the kitchen while she was cooking was a blatant rip-off of Neo in The Matrix conversing with the Oracle in her kitchen while she made cookies? Should I question how Mack’s character, who was supposedly seminary trained, could ask the most inane questions of God, that any student who went to an institution worth its salt, or for that matter, any laymen who’d spent any decent amount of time with the Bible should know?

What boggles my mind is that a number of well-respected individuals do consider The Shack to be good literature. One endorsement comes from Eugene Peterson, an individual I admire very much and happen to be reading currently. Of The Shack, Peterson says this:

When the imagination of a writer and the passion of a theologian cross-fertilize the result is a novel on the order of The Shack. This book has the potential to do for our generation what John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress did for his. It's that good!

The Shack equated to Pilgrim’s Progress? Really? Seriously? I read that and it makes me wonder if Peterson actually read the book. I don’t mean that as an insult against him. Regularly, well known individuals are approached by publishers, given a synopsis of a book, and then an already written endorsement for the individual to sign. Most of the endorsements you see on the back covers of books are handled this way. Endorsements should be evaluated with more than a grain of salt.

Yet, I could see why someone like Peterson would appreciate the concept of The Shack simply because of the way he sees the communal nature of the Trinity. In Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places, Peterson writes,

Trinity understands God as three-personed: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, God in community, each “person” in active communion with others. We are given an understanding of God that is most emphatically personal and interpersonal. God is nothing if not personal. If God is revealed as personal, the only way that God can be known is in personal response. We need to know this. It is the easiest thing in the world to use words as a kind of abstract truth or principle, to deal with the gospel as information. Trinity prevents us from doing this.

The premise of The Shack promises what Peterson describes above; unfortunately it does not satisfyingly deliver. And that’s the key question--does The Shack really satisfy? Ask yourself that if you really liked the book. Strip away the way the persons of the Godhead were presented in very likable portrayals. Strip away the meal time conversations, the walking on water across the lake, and ask yourself if you really know God better.

Here’s the problem: ultimately we are not given real answers by God in The Shack. Rather we are given answers as best as William P. Young understands God and can speak for God. See, in any work of fiction, the writer is ultimately God. The writer sets the events in an absolute predetermined way, and all characters--even God himself as a character--will speak and behave only in how the true god of the story (the writer) thinks they should. I’m not trying to be harsh here, but I’m trying to remind readers of this very important fact: The Shack does not contain a message from God; it contains a message about God from the writer--a writer whom to my knowledge hasn’t received any more revelation from the real God than you or me. This writer did the best job he knew how, but ultimately, he doesn’t really give us anything new and certainly nothing revelatory about God and our relationship to him.

And frankly, it saddens me that so many have so uncritically embraced the book. You don’t have to be a theologian to see problems in The Shack. Kathy does not consider herself a theologian at all, but as we were listening to the audio version, she offered a blow by blow commentary of its weaknesses as we listened. The book right now has almost 3000 reviews on Amazon.com. One reviewer, who said he liked the book, but gave it only three out of five stars noted that he was very concerned by the “book being embraced with nothing but naive, uncritical, and untempered enthusiasm.” This concerns me as well.

My friend Todd Benkert has written about the popularity of The Shack, trying to figure out why it’s been so very popular for a self-published book. In his blog post, “One More Post about The Shack with ‘Something Else’ to Consider,” Todd offers this theory:

The Shack offers people what the church, by and large, does not--hope for and acceptance of messed up people.

Mack is a messed up person. He has real hurts. He has experienced real pain. He does not act and think the way a Christian ought to act and think. In fact, he questions and even blames God for what has happened to him. People relate to Mack. They relate to the pain and hurt and struggle and questions Mack has. And they find from Papa, Jesus, and Sarayu the kind of understanding and acceptance that is, for whatever reason, missing in the church.

Todd may very well be on to something. My concern is that while the Church does indeed need to get its act together in regard to people who are hurting, The Shack is not really a solution. It’s a band aid for a much more serious kind of wound. Think about this really-- if you knew someone who had lost a child through murder or some other tragic means, would you really consider giving The Shack to a hurting person to read? I cannot fathom that idea.

And I know that many people who’ve appreciated The Shack feel as if they can relate to God better after reading the book. But if someone wants to know what God is like, rather than handing them a copy of The Shack, (and pardon me if this sounds unnecessarily church) I’d give them a copy of the New Testament. In the Gospels, we learn how God “became human and made his home among us.” In doing so, not only did he provide a way for us to be reconciled to him, he also “put on a face” in the person of Jesus. You want to know what God is like? Read the Gospels. Do you want to know specifically what the Father and Son are like and how they interrelate? Engage in a good study of Jesus’ parables. If you’re curious to know how to relate to the Holy Spirit, read the Book of Acts. God has revealed himself already through his Son and through his written Word. If you still cannot relate, it may be your translation of the Bible. Be sure you are reading something translated in the last decade or so in normal, contemporary English.

I have no trouble recommending the New Testament as a way of relating to God. That’s one of its major functions. But sadly, I cannot recommend The Shack under any circumstances or in any contexts.

For Further Reading:

Lest anyone accuse me of not giving equal time, here are two reviews a little more positive worth considering:

- “Reading in Good Faith” by Derek Keefe - Acknowledging there are problems in the book, Derek Keefe finds some value in The Shack that the church can benefit from.

- “The Shack by King David” by Gordon MacDonald - MacDonald wonders if anyone took offense when David portrayed God as a smelly, dirty shepherd in Psalm 23.

Thursday, June 4, 2009 at 10:19AM

Thursday, June 4, 2009 at 10:19AM  Yesterday, via Twitter, I received confirmation from Keith Williams, Bible editor at Tyndale House, that the upcoming Mosaic Bible will have wide margins (of some sort). Currently, no printing of the second edition (2004, 2007) NLT Bible has any significant room for personal notetaking. The first edition (1996) NLT Bible was available in a printing known as the Notetaker’s Bible, which--in my opinion--had the best layout for making personal notes of any Bible I’ve ever seen. Unfortunately, it was a weak seller (it didn’t have the advantage of a strong NLT blogosphere base at the time, no doubt) and after going out of print, it was never re-released in the second edition NLT.

Yesterday, via Twitter, I received confirmation from Keith Williams, Bible editor at Tyndale House, that the upcoming Mosaic Bible will have wide margins (of some sort). Currently, no printing of the second edition (2004, 2007) NLT Bible has any significant room for personal notetaking. The first edition (1996) NLT Bible was available in a printing known as the Notetaker’s Bible, which--in my opinion--had the best layout for making personal notes of any Bible I’ve ever seen. Unfortunately, it was a weak seller (it didn’t have the advantage of a strong NLT blogosphere base at the time, no doubt) and after going out of print, it was never re-released in the second edition NLT. NLT in

NLT in  Faith & Reason

Faith & Reason